How Can Business Help?

There are many reasons why people move. Whether it be for work, new opportunities, family or for fear of persecution, the UN estimates that the number of people who live in a country other than where they were born far exceeds 244 million (a 41% increase compared to the year 2000). Vast numbers of these are vulnerable people at risk of exploitation and modern slavery. How can business play its role in tackling the illegal and exploitative treatment of vulnerable people ‘on the move’? This paper explores different legal frameworks, initiatives and business tools that tackle exploitation and ultimately ensure ethical treatment of people ‘on the move’ as they seek and enter new employment.

The United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs) is the overarching framework that captures the expectations of governments, corporations and civil society in relation to human rights. This internationally recognised framework outlines the state duty to protect human rights, corporate responsibility to respect human rights and the importance of access to remedy. The UNGP’s provide an invaluable starting point to launch this discussion, as both the actions of the state and corporations have a significant impact on the protection and enjoyment of an individual’s rights. In this insight, I will focus in on the specific responses to the protection of the rights of refugees and migrants as two categories of people ‘on the move’.

Refugees

“Refugees are people fleeing conflict or persecution. They are defined and protected in international law, and must not be expelled or returned to situations where their life and freedom are at risk.” (UNHCR definition)

From a moral perspective, granting asylum to those fleeing persecution in foreign lands can be argued to be one of the earliest marks of ‘civilization’; evidence of this can be identified as early as 3,500 years ago during the early empires in the Middle East such as the Hittites, Babylonians, Assyrians and ancient Egyptians. However, when we look to the legal history, we need not look so far back. The codification of refugee protection into international law is only a few decades old and can be dated back to the creation of the United Nations, most specifically to Article 14(1) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which was adopted in 1948 and guarantees the right to seek and enjoy asylum in other countries. This was further underpinned by the establishment of the UN High Commission for Refugees (1950) and the UN Convention relating to the Status of Refugees (1951) – which altogether provided the legal foundation for protecting refugees. Notwithstanding the fact that its initial mandate ran for just three years, the need for this international function has been demonstrated many times over.

Although not without its flaws, the UN framework has provided 20 million refugees access to a legal structure that accounts for their precarious position. With the increased movement of vulnerable people around the world, governments and (increasingly) businesses are having to face up to the reality of the smuggling and trafficking of people – notorious examples include the exploitation of Syrian refugees in the Turkish garment sector supplying UK high street brands, exposed by the BBC’s Panorama in October 20161.[1]

While such unacceptable conditions are often by design hidden from international view, a number of companies have responded with strong and clear commitments to ensure the protection of these vulnerable people. Marks and Spencer, for example, has called out its response to the Syrian refugee exposé in its 2017 human rights report[2]. The leading UK retailer was able to transparently describe the actions in response and the steps taken to prevent this from happening in the future. Admirably, Marks and Spencer was also able to demonstrate knowledge of the complexity of the issue:

“This case prompted us to reflect on the enhanced risk of modern slavery where third party labour providers are used, wherever this may be in our business or supply chains. The realities facing migrants mean that they will take any measures to find work, putting themselves at risk of modern slavery and forced labour. We recognise that traditional audits do not always highlight these potential risks and so in the future, we will engage from the outset with the systemic issues which underlie such cases.” (page 15 of the Marks and Spencer “Our approach to Human Rights”, 2017)

Migrants

“Migrants choose to move not because of a direct threat of persecution or death, but mainly to improve their lives by finding work, or in some cases for education, family reunion, or other reasons. Unlike refugees who cannot safely return home, migrants face no such impediment to return. If they choose to return home, they will continue to receive the protection of their government” (UNHCR definition)

Although migrants are still able to receive protection from their governments, they are nevertheless susceptible to exploitation, especially through human trafficking. One initiative, which is focussed on the Asia Pacific region and has been in place since 2002, is the Bali Process on People Smuggling, Trafficking in Persons and Related Transnational Crime (the Bali Process) [3]. This forum for policy dialogue and information sharing has sought to raise awareness of the consequences crimes related to migration. The UK supports as an observer and at the 2017 meeting said: “Tackling modern slavery requires global collaboration: modern slavery often crosses borders, as do the organised criminal networks which seek to exploit those most vulnerable for profit.”

An exciting development of the Bali Process in August 2017 was the formal inclusion of the private sector through the launch of the Bali Process Government and Business Forum to eradicate these crimes. The Bali Process considers the complexity and growing scale of the migration challenges and estimates its reach to cover 4.5 billion of the world’s population. Now, through this new initiative, CEOs and business leaders will advise government on how to prevent and combat human trafficking and related abuses, and share experiences on best practice.

Furthermore, the Institute for Human Rights and Business (IHRB) [4] development of the Dhaka Principles for Migration and Dignity [5] provides a set of human rights-based principles to enhance respect for the rights of migrant workers from the moment of recruitment, during overseas employment and through to further employment or safe return to home countries.

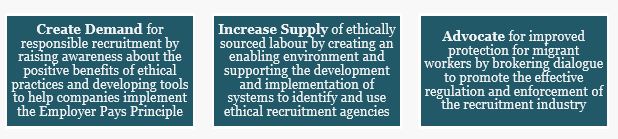

More recently, building on this helpful set of principles, IHRB launched the Leadership Group for Responsible Recruitment, a collaboration between leading companies and expert organisations to drive positive change in the way that migrant workers are recruited. Its core aims of ensuring equal treatment, freedom from discrimination and protection of law for all workers, are supported by ten specific principles. The first principle – that no fees shall be charged to migrant workers seeking employment – is being tackled by the Leadership Group for Responsible Recruitment, set up in May 2016. The Leadership Group’s aim is bold – the total eradication of fees being charged to workers to secure employment and plans to achieve this through three primary methods:

To find out more about how your business can tackle the issues of ethics when people are ‘on the move’ contact Sancroft on: [email protected] or 0207 960 7900.